By Eileen Nchanji, Grace Nanyonjo, and Isaac Muggaga

Common beans are a valuable crop across sub-Saharan Africa, contributing to food nutrition security and income for smallholder farmers. It was considered a subsistent crop mainly grown by women for food; with the excess sold to get money for other household needs. In most cases, women who grew and sold beans controlled how the proceeds from this crop were used. The Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, Harvest Plus, and the National Agricultural Research Systems have promoted and raised awareness of beans and partnered with governments and development partners to enact policies that promote the consumption of beans as grain and bean-based products. The commercialization of beans has resulted in changing gender roles, with women still heavily involved in the production and retail markets and men selling in regional and international markets; deciding on how the money from the bean sales is used. This is not only the case with beans but other crops – maize, rice. Groundnut and French beans have moved from being subsistence to commercial status in Africa cited in Nakazi et al 2017.

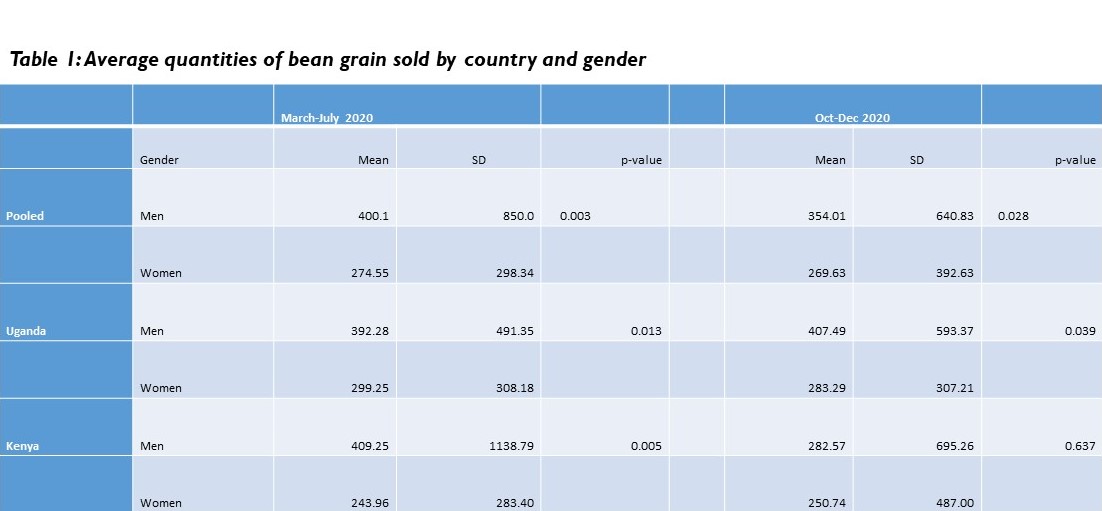

In a recent study funded by International Development Research Centre and the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research in Uganda – Central Bean corridor and Kenya (Western, Rift valley, and Eastern Bean corridor) we discovered that more men marketed beans than women in Uganda, while more women marketed beans than men in Kenya. In the March to July season, 92% of men and 87% of women in Ugandan households marketed beans, while 87% of men and 82% of women marketed beans in the October December season. In Kenya, 67% of men and 73% of women marketed beans in the March to July season, while 53 % of men and 61 % of women were in a recent study in Uganda and Kenya. There was a significant difference (p<0.05) between quantities of grain sold by men and women in both seasons in Uganda. There was a significant difference (p<0.01) only in the March to July season but no difference between quantities marketed by men and women in October to December season in Kenya shown in Table 1.

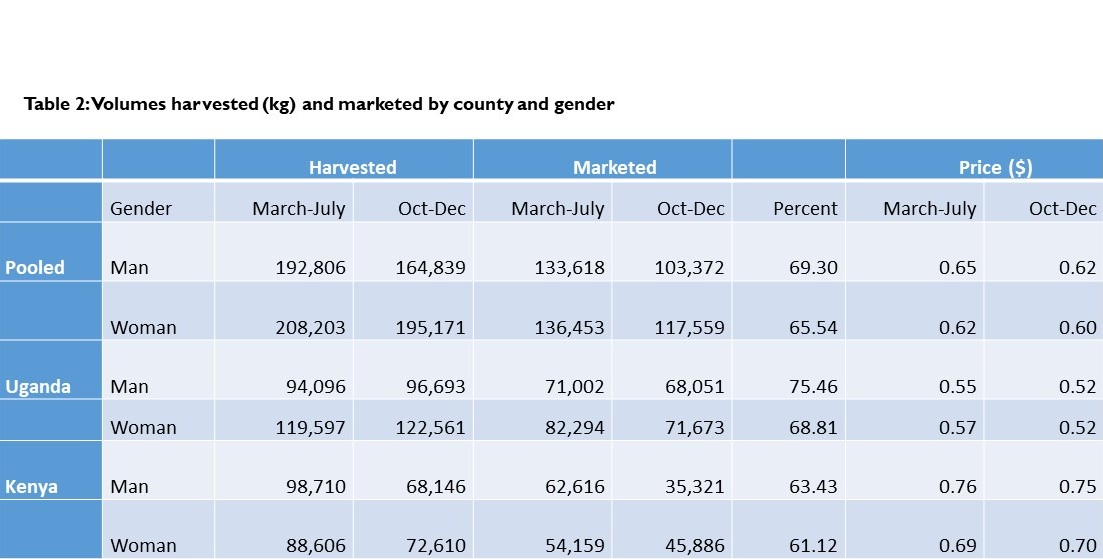

Men in Uganda marketed 6% more of what they harvested, while the difference between the men and women was 2%. A larger proportion of what was harvested was marketed in Uganda compared to Kenya, and women in Uganda also sold proportionately more than men in Kenya. There was a slight variation in the selling prices by men and women in Uganda during the long rainy season, with women selling at a slightly higher price of $0.57 per kg compared to men’s $0.55. The price dropped to $0.52 for both during the October to December seasons. In Kenya, the men consistently sold beans at a higher price than women, $0.76 against $0.69 in March to July and $0.75 against $0.70 in October-December, without much seasonal variation in prices. The difference in prices between men and women may be due to the type of markets they could access and the period when they sell the beans. The farther and more structured the market, the better the bean prices. These reasons may explain why men’s bean prices were comparatively higher in the Kenyan site as shown in Table 2.

Men’s control of family income is embedded in gender relations and sometimes resulting in domestic abuse and battering of women when they oppose. This was confirmed in men focus group discussion in Serere where a respondent said:

The whole family managed the plot, but when it comes to sharing the proceeds, I decide the amount that goes for school fees and other home needs. I am the chairman in my home, so when it comes to management, I direct my family on what to do and when to harvest. 80% goes to school fees first. As the chairman, I decide the amount that goes to each requirement at home.

As a result, women producers find it challenging to maintain a profitable market and are not able to cater to their basic needs. In cases where there is joint decision-making on household needs, the excess reflects the needs of the man and not that of the women. Studies have been carried out to explain what household incomes are usually spent on, with resulting pointing to the fact that women spend on food, children need, labor, and fertility preferences while men additionally spend on alcohol and tobacco. In Tanzania, with cash crops no longer profitable, some of the financial burdens have shifted to women. Women currently take care of expenditure once thought to be the sole responsibility of the man. For example, women in Iboja District, through focus group discussions complained that their spouses sold crops when it was not yet ripe for harvest and used the money to buy alcohol.

In a women focus group discussion in Soroti, a respondent shared:

It is my husband who sold the sweet potatoes. On his return home, he gave me only Ugx 12000/= (US $ 3) and said the rest of the money was supposed to cover mobile money withdrawal charges, yet he was supposed to bring Ugx 53,000 (US $ 14.48).

Another female respondent said, “My husband deceived me that he was not paid last season, so this season I am ready to go with him to the store as I have learned a big lesson from last season.’’ According to the women, men mostly use the family income for unproductive purposes, thus rendering a woman’s time, physical and financial resources useless with a negative impact on the household’s economic status.

According to another respondent in the men focus group discussion in Serere:

Most of the causes of gender-based violence or domestic abuse are rooted in the allocation of money from the sales of agricultural produce. Usually, after selling the produce, men take all the money, forgetting other family members who participated in the production process. That is when domestic violence starts. I get so many of such cases

In cases where women decide on the use of the money from the sale of any of the agricultural produce. They say their spouses denied their financial support and left all home responsibilities to them. The women take care of food, fuel, medicine, and even pay the school fees of the children. Men said this was a strategy to control women’s economic empowerment so that they are within the cultural expectations and socialization, so women do not over-take the men as the household heads.

The choice between practical and strategic empowerment becomes important where the former involves improvements in women’s ability to achieve more without necessarily challenging the basis of gender relations while strategic empowerment on the other hand involves challenging the gender status quo and women’s ability to make decisions over the income incurred from the sale of agricultural produce.

In a bid to increase women’s control over income from the agricultural sale. The Pan Africa Bean Research Alliance (PABRA) in partnership with MasterCard deployed the MasterCard Farmer network (MFN), a financial inclusion platform that digitizes marketplaces, payments, workflows, and farmer financial histories within the agriculture sector. This tool connects farmers, especially women, to markets and formal financial services digitally in tandem with their needs. To solve the challenges of access to credit by women, the MFN model pegs the transaction history of women as collateral to access loans from the banks that are linked to the platform. As linking more women and youth to financial institutions are likely to accelerate their production and market involvement. We expect women to excel in their agricultural enterprises and make decisions on money received digitally in their accounts after selling their agricultural produce.

As much as the MFN innovation has been embraced by men and women farmers, there are still challenges such as extra fees on mobile payments. Women in focus group discussion shared:

Mobile money would be good without the extra charges associated with sending and withdrawing money. The network also makes it difficult to access and use money. If charges for Ugx 100000 to 1 million are capped at Ugx 2000, then that is okay.

The issue of extra fees charges also applies to banks; these charges apply whether there is money or not in the account. Mobile money is preferred to banks because of the convenience and access to mobile money agents. For example, the distance to a bank agent is 5.43 km and a mobile agent is 2km. According to a woman farmer, another challenge is that “it is my husband who withdraws the money because he owns the phone. He can lie that they have sent a less the amount yet he received all the money.”

As we continue to promote digital financial inclusion, two gender focal persons were trained to mitigate the effects of gender-based violence through education and awareness creation exercises in partnership with the power holders within these communities.