By: Radegunda Kessy, Sylvia Kalemera, Fadhili Kasubiri, Patricia Onyango, Owen Kimani, Jean Claude Rubyogo

For the longest time when one mentions Maasai, the image that comes to mind is of young men—warriors—living in the wilderness, moving their livestock from one seasonal pasture to another, coping with the vagaries of nature and the dangers of attack from wild animals. This image is slowly changing as pastoralists experience climate change threats to their social, cultural, and economic statuses in various sectors, especially the livestock sector; therefore, hampering the livelihoods of pastoral communities. Traditionally, pastoralist communities migrate to search for good pastures and water in other areas far from their homes for a long time before they come back. The habit does not give them time to produce food from crops. They depended mostly on animal products such as milk and meat. Today, it is impossible because many places have been occupied by people and the scarcity of water is felt everywhere. The situation has forced the Maasai community to stay in one place and look for supplementary sources of food and income besides relying entirely on their herds. The decrease of grazing land and water scarcity caused by increased population and climatic change effects has forced major changes to pastoralist communities’ lifestyles to tackle some of these challenges. Because of this, the Maasai’s interest in other crops sparked! They started farming other crops among them common bean.

Livelihood diversification through the adoption of agriculture

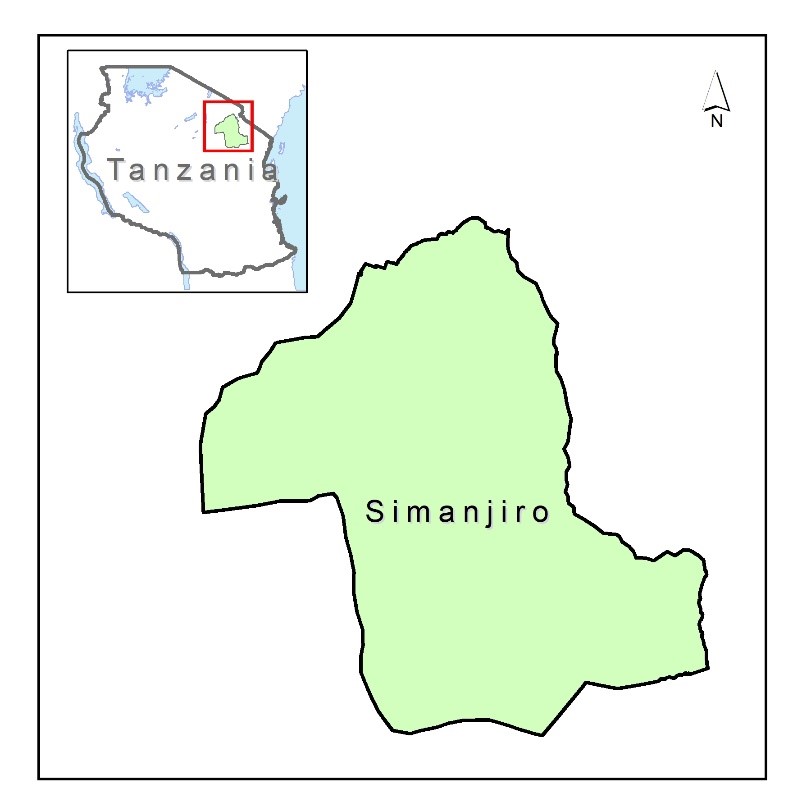

The Maasai pastoralists are diversifying their source of livelihood by engaging in agricultural production to complement livestock farming. The adoption of cultivation by the pastoral Maasai community is widely practiced to diversify their diets in the Simanjiro district of Manyara region, South of Arusha, Tanzania (Figure 1). In Tanzania, beans are considered a key crop because of its nutritional, economic, and social benefits. Consumption of common beans is a nutritious alternative source of protein to the pastoralist community. Despite the opportunity to embrace agro-pastoralism, the pastoralists face the challenges of access to technical skills, improved inputs such as seed, chemicals, and other important technologies. Pan Africa Bean Research Alliance (PABRA) is working to promote these technologies to get to the agro-pastoralist to bean farming.

Contribution of research and development towards a secure food system

Simanjiro District, mostly a semi-arid zone lies on the Maasai steppe. About 85 percent of its inhabitants are Maasai pastoralists. From 2015 to 2017, the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT-Alliance through the PABRA, supported by the Scaling Seed and Technology Partnership (SSTP) a USAID supported the program through the Alliance for Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) launched a 27 months’ project ‘’unlocking the potential of seed companies to reach smallholders with new improved bean varieties in northern Tanzania’’. This project aimed to contribute to food and nutrition security and incomes of smallholder farmers in Simanjiro district, through multiplication and equitable access to quality seed of improved bean varieties. The project started by identifying key community champions who could influence the community members on how to incorporate various crops to their food products that will complement their livestock keeping and products. The project team in collaboration with Tanzania Agriculture Research Institution (TARI) Selian and the district council of Simanjiro organized field demo plots that gave farmers an opportunity to compare the quality seed of improved varieties vis a vis farm-saved seed that they used to plant (Figure 2). The quality seed of improved varieties was bundled with information on agronomy, the use of fertilizers, and agrochemicals for pest and weed management. Thanks to the contributions of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Global Affairs Canada, and Swiss Development Cooperation, the African Development Bank through the Technologies for African Agricultural Transformation (TAAT), beneficiaries like Matthew continue to access quality seeds to enhance bean productivity in Simanjiro and beyond.

The process was very participatory with the list of varieties and their traits shared with the farmers. They were allowed to choose their variety of preferences for home use and for the market. The District Council of Simanjiro did a good job on community mobilization and identification of champion farmers in the community who could host demonstration plots on behalf of the community. Women were not left out of the process. Other value chain actors were also present, and the private sector offered various technologies, services, and products including mechanization (figure 4&5).

Farmers got interested and started growing maize and beans on their farms. In comparison to the two crops (maize and beans), there are indications that beans did extremely well and were mostly eaten in their homes. Currently, their eating habits have also changed from the usual meat and milk products to cereals.

Mathew Alaigutu, one of the champion farmers shares, “Currently we eat ‘ugali’ and beans or leafy vegetables, rice and beans, potatoes and beans. We now eat beans more frequently compared to meat and milk. If a household has beans, they can survive without going long distances in search of vegetables in the markets. Our children can no longer feed only on milk and meat as it is in the past. I have a son in a private secondary school in Arusha and each year I need to pay his school fees of Tsh 3,708,800.00 (US $1,600) of which a large percentage comes from the beans I sell. One of my friends in our village pays school fees for his four sons in secondary school using income from beans as well. We are also buying cows to restock our herd. Through beans, I meet with other farmers and we talk about improving the crop. I currently own a tractor on the farm. I plan to lease it to other farmers for their land preparation. This investment will bring in more money and I can even train one of my sons to operate it. This year in August, I was identified as a progressive farmer by the district council and was invited to display beans from my farm which got sold at a price of US $ 1,400 per kilogram.”

As in other Sub Saharan Africa, agro-pastoralists women from Simanjiro are also keen to ensure food security in their household. This was also testified by Martha Samwel who also keeps livestock. ‘We produce maize and beans mainly for food and selling the surplus. Our diet is more diversified now compared to previous days. We can eat ugali with beans or leafy vegetables and a glass of milk to improve the diet. Common bean farmers have a better chance of improving income than maize farmers because beans are stable crops and mature earlier than maize. In the future am planning to produce beans solely because of stable price in the market. Money that we get from selling the surplus of beans we buy more livestock because it is difficult to keep the cash.’

The market in Simanjiro district prefers red mottled and yellow beans. They are highly marketable and do well in this region. Farmers are highly motivated to expand their investment in beans in terms of the number of acreage and purchase of farm implements (Figure 6 & 7). Elinei Kihwera who works with BEULA seed company reported an increase in demand for improved bean seeds from 0.8 tons in 2017 to more than 70 tons in 2020 following a promising performance in yield, quality, and market preferences.

After accessing the quality seed of improved varieties, farmers expanded production, therefore making their products more visible and attractive to the buyers. Farmers invested in technologies that helped them to manage the scale of production. As they increased the acreage under beans, so did the demand for labor. As stated by Mathew, many people from neighboring regions such as Singida traveled to Simanjiro during the harvest because they were sure of making money from the services to the farms. Traders were also busy and went from farm to farm checking on the produce and negotiating better prices and gauging the quality of the produce (figure 8).

Through bean seed promotion conducted by the Alliance and TARI, BEULA seed company saw a business opportunity in Simanjiro to supply beans and maize seeds as well as input supplies to the farmers around that district. The company has also contracted some farmers as out-growers of seeds to make sure that seed availability is resolved. “Seed multiplication plots continue to save as part of promotion because of their performance compared to farmers’ field. Close to the new season, farmers would start asking about the seed they saw during the multiplication” Kihwera stated.

“Following the field expansion, the Alliance is currently working with other stakeholders to bring in other technologies, especially mechanization to increase efficiency and reduce drudgery to farmers especially women who do manual seed sowing and threshing. Imara Tech, a multi-crop thresher fabricator company has been linked to providing these services to the farmers in Simanjiro. Mathew and other farmers around this area will benefit and save the costs of labor during the harvest. Besides coaching farmers on seed multiplication, the link with Crop Bioscience Solution and Rikolto will help to access planting and crop management services such as spraying. The two organizations have trained farmers – especially youth – on the use of technologies as the solar bubble drier. Such technologies are bound to improve bean productivity among farmers and maximize their profits from the sale of premium beans and improve their nutrition.”